For as long as people have been inventing reasons not to get real jobs, there have been writers. They are a strange and fragile species, sustained mostly by coffee, nicotine, validation, and the lingering hope that one day their suffering will be monetized.

Writers are said to have “habits,” which is a generous word for “methods of procrastination.” They wake early, or they don’t. They write daily, or weekly, or in bursts of manic productivity right before a deadline. There is no wrong way to be a writer, as long as you are constantly disappointed in yourself.

The process begins with inspiration, that elusive moment when an idea strikes, usually in the shower, while driving, or during someone else’s conversation. Most ideas die before ever reaching paper, which is probably for the best. The few that survive are immediately overthought, expanded into twenty-page outlines, and abandoned once the writer realizes they have no idea how stories actually end.

Some great authors had famously consistent routines. Hemingway wrote standing up, because sitting would imply comfort. Maya Angelou rented hotel rooms solely to avoid her own furniture. Stephen King writes 2,000 words a day, which makes the rest of us feel like we’ve been wasting oxygen. In short, all the greats found ways to make writing feel like punishment, which is why they’re remembered, and we’re still on social media.

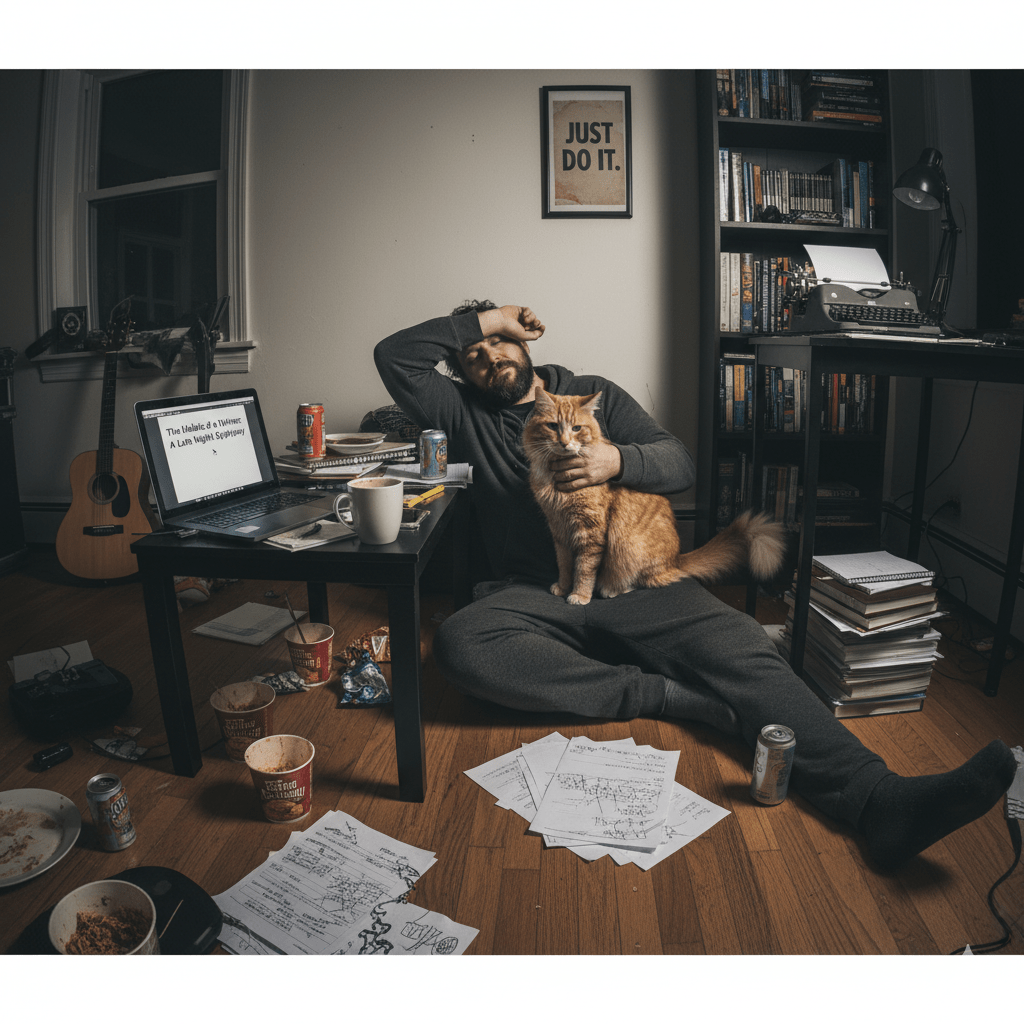

The modern writer begins their day by “warming up,” which means opening social media to check out cat memes, watch funny police videos, and to compare their mediocrity with others. This activity can last anywhere from ten minutes to the entire lifespan of a star. The actual writing starts only when guilt outweighs self-loathing, or when a pet looks genuinely disappointed.

Writers speak often of “the muse,” an imaginary force, usually a beautiful woman, blamed for both their brilliance and their laziness. When inspiration strikes, it feels divine; when it doesn’t, the muse is apparently “on break.” In reality, the muse is just caffeine and fear having a team meeting.

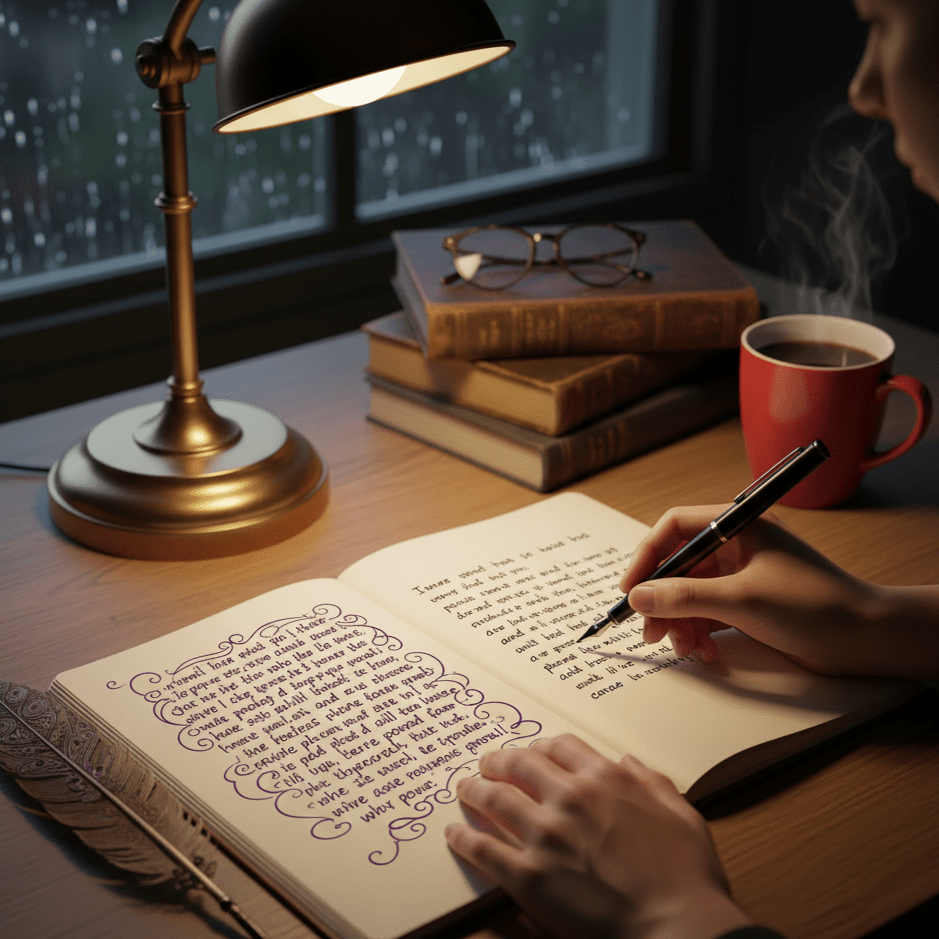

Writers are famously attached to their tools. Some swear by typewriters because they make a satisfying sound that suggests productivity even when the words are garbage. Others prefer laptops, which allow for seamless access to distraction and the illusion of professionalism. The notebook crowd insists that handwriting connects them to their soul, though mostly it connects them to a pile of half-finished thoughts no one can read, including the writer.

The only tool that really matters is Wi-Fi, which must be both strong enough to procrastinate on and weak enough to complain about.

Writer’s block is what happens when a writer can’t decide whether their bad ideas are bad because they’re bad, or because they’re not yet misunderstood genius. It is both a creative crisis and a convenient excuse. Non-writers call it “being lazy,” but writers know it’s far more complex; it’s “being lazy with a narrative.”

Some claim to overcome writer’s block through discipline, but most of us prefer to wait it out dramatically, like a Victorian invalid. Nothing says “artistic” like lying on the floor declaring that language has betrayed you.

Editing is where the real writing happens, which is why no one enjoys it. It’s the stage where the writer realizes the story they wrote is not the story they meant to write, and may in fact be about a completely different person in a different century. The process involves deleting everything that seemed clever at 2 a.m. and trying to pretend it never existed.

Eventually, a moment comes when the writer declares the work “done,” a word that means “I can’t look at this anymore without vomiting.” The draft is sent off, and the cycle begins again… proof that writing is not a profession so much as a recurring fever dream with punctuation.

In the end, the writer’s greatest habit is persistence, or delusion, depending on who you ask. They keep at it, convinced that one day they’ll produce something brilliant enough to justify the years of unpaid staring. Until then, they’ll sit at their desks, sipping lukewarm coffee, rearranging commas like chess pieces, and insisting that this, all of this, is part of the process.

And maybe it is. Or maybe it’s just easier than admitting they don’t know how to do anything else.

Leave a comment