Every writer has heard it. Usually from someone who has never written a book. Sometimes from a teacher who means well. Occasionally from a relative who thinks they’re being helpful while also wondering why you don’t have a “real job.”

“Write what you know.“

It sounds wise, doesn’t it? It sounds safe. It sounds like the kind of advice you might find inside a fortune cookie that was written by a committee of accountants. But let’s pause and examine this phrase with the kind of scrutiny normally reserved for suspicious leftovers in the fridge.

Because here’s the truth: “Write what you know” is terrible advice.

Here’s the problem with the fortune cookie method. Imagine if chefs only cooked what they knew. We would all be eating the same three meals forever. Imagine if musicians only played what they knew. Every concert would be a cover band. Imagine if explorers only traveled where they already lived. The maps would still say “Here Be Dragons” because nobody would have bothered to check.

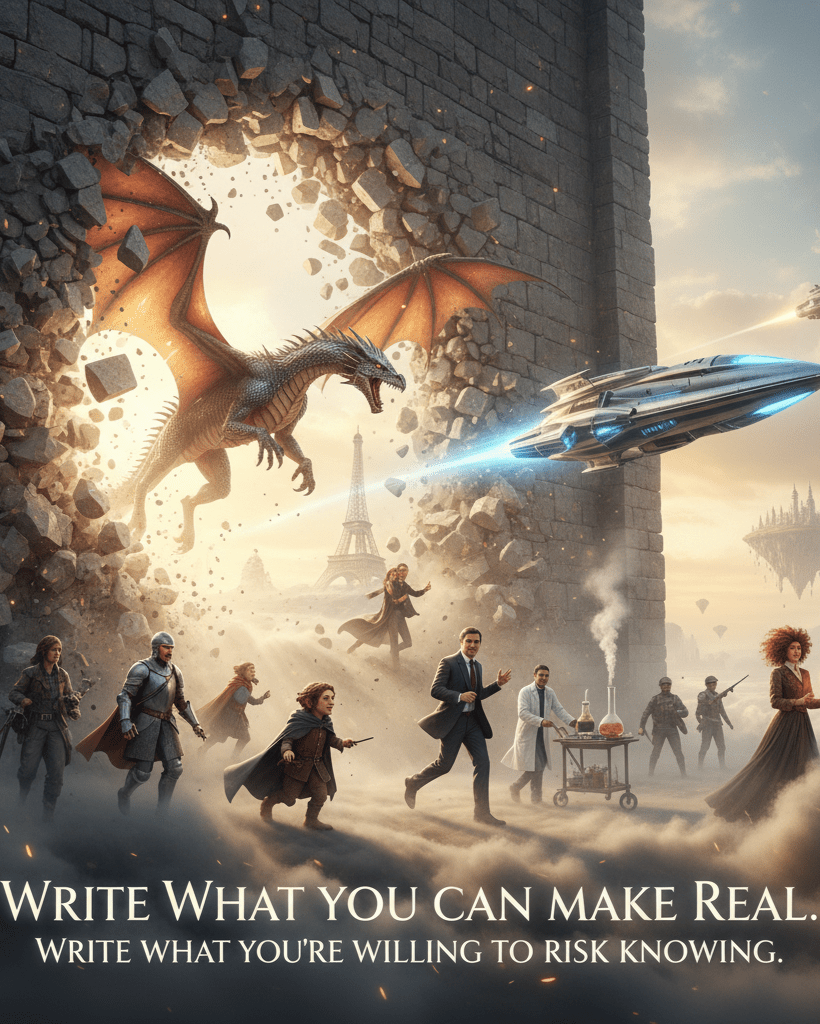

Writing isn’t about staying inside the walls of your own experience. Writing is about breaking them down, climbing over them, and occasionally setting them on fire for dramatic effect.

If writers only wrote what they knew, we would have no dragons, no starships, no courtroom dramas unless the author happened to be a lawyer. We would have no hobbits, no dystopias, no romances set in Paris unless the author had personally dated someone under the Eiffel Tower.

The advice collapses under its own weight.

What Do We Mean by “Know”?

The real problem is that the word know is slippery. Does it mean:

Personal experience?

Emotional truth?

Research?

Something you overheard once in a coffee shop?

If “know” means personal experience, then only astronauts can write space operas, only surgeons can write medical thrillers, and only vampires can write vampire novels. Which is inconvenient, because vampires rarely submit manuscripts on time.

If “know” means emotional truth, then the advice is redundant. Of course, you must write emotions you understand. Fear, love, grief, joy… these are the currencies of fiction. But you don’t need to have fought in a war to write about courage. You don’t need to have robbed a bank to write about desperation. You just need empathy, imagination, and the willingness to research until the unfamiliar feels normal.

If “know” means research, then the advice is misleading. It should say “Write what you’re willing to learn.” That would be honest. That would be useful. That would save writers years of confusion.

What do writers actually do? Writers invent. Writers extrapolate. Writers stitch together fragments of reality and imagination until the seams disappear.

Tolkien didn’t “know” hobbits. He knew languages, myth, and human nature.

Mary Shelley didn’t “know” how to reanimate corpses. She knew grief, science, and the fear of human ambition.

Octavia Butler didn’t “know” the future. She knew history, injustice, and the patterns of human behavior.

Every great work of fiction is built on things the author didn’t literally know. What they knew was how to make the unfamiliar feel real.

So let’s retire “Write what you know.” Let’s replace it with something more honest.

Write what you can make real.

Write what you can imagine with conviction.

Write what you’re willing to research until it feels real.

Write what you’re willing to risk knowing.

Because writing isn’t about comfort. Writing is about risk. It’s about stepping into the unknown and dragging your readers with you, whether they like it or not.

Research is your best friend. If you want to write about something you don’t know, research is your ally. Research is the difference between a believable courtroom drama and a scene where the lawyer shouts “Objection!” at the wrong time.

Research isn’t just about facts. It’s about texture. It’s about the smell of a hospital corridor, the rhythm of military jargon, the way a pilot checks instruments before takeoff. These details make the unfamiliar feel lived in.

And here’s the secret: research is fun. It’s procrastination disguised as productivity. It’s the excuse to read strange books, interview fascinating people, and spend hours on YouTube watching videos titled “How to Survive a Medieval Siege.”

Facts alone are not enough. You also need empathy. You need to understand how people feel in situations you have never experienced.

You don’t need to be a soldier to write war. You need to understand fear, loyalty, and loss. You don’t need to be a doctor to write medical drama. You need to understand urgency, responsibility, and exhaustion.

Empathy is the bridge between what you know and what you don’t. It allows you to translate human emotions into any context.

Curiosity is the reason writers can write about anything. Curiosity is the permission slip to explore.

When you write about something you don’t know, you are not faking it. You’re discovering it. You’re learning as you go, and your readers are learning with you.

This is why “Write what you know” is terrible advice. It discourages curiosity. It tells writers to stay in their lane. But writing isn’t about lanes. Writing is about detours, shortcuts, and occasionally driving straight through the cornfield because you want to see what happens. Of course, I wouldn’t recommend that unless you own the cornfield and the car.

So what should writers actually do?

Research until you know everything, then keep researching until you know more.

Don’t stop at Wikipedia. Read memoirs, watch documentaries, talk to people who have lived through it.

You don’t need the same experience. You need the ability to feel those experiences.

Stay curious. Let writing be the way you discover what you don’t know.

Risk knowing. Be willing to step into the unknown, even if you stumble.

The Snack theory of writing is my personal favorite. Let’s pause for a snack. Because writing advice is easier to digest when paired with food metaphors.

“Write what you know” is like telling someone to only eat snacks they’ve already tried. Safe, boring, predictable. But the joy of snacks is discovery. The strange flavor of a new brand of crisps, the new pastry, the candy from another country. Writing should be the same.

Try the unfamiliar. Taste the unknown. If it’s terrible, spit it out and try again. If it’s wonderful, share it with everyone.

The Danger of Comfort is the real danger of “Write what you know”. It keeps writers comfortable. Comfort is the enemy of creativity. Comfort produces safe stories, predictable plots, and characters who feel like cardboard cutouts.

Risk produces discovery. Risk produces originality. Risk produces the kind of stories that make readers sit up and say, “I’ve never seen this before.”

Let’s imagine a circle. Inside the circle is what you know. Outside the circle is what you don’t know.

If you only write inside the circle, your stories will be small. If you step outside the circle, your stories will expand. The circle itself will grow. What you don’t know will become what you know.

This is how writers evolve. This is how imagination works.

So let us say it clearly: “Write what you know” is terrible advice because it mistakes comfort for creativity.

Better advice? Write what you’re willing to risk knowing. Write what you can make real. Write what you can imagine with conviction.

Because if writers only wrote what they knew, we would all be stuck reading memoirs about grocery shopping. And while that might be fascinating for one chapter, nobody wants twelve volumes on the history of your local supermarket.

Writing isn’t permission. Writing is participation. It’s the act of stepping into the unknown and inviting readers to join you.

So don’t write what you know. Write what you don’t know yet. Write what you’re willing to discover. Write what you’re willing to risk. Write what gives you passionate feelings. If you aren’t passionate about what you’re writing, then your readers won’t be either.

That is how stories are born. That is how imagination survives. That is how literature evolves.

Leave a comment