How Point of View Shapes Power

In every scene, a writer chooses a place to stand with the camera. That choice lives inside every sentence, even when a writer never mentions a “camera” or a “gaze.” A writer decides whose body the reader feels from the inside, whose body the reader observes from across the room, and whose interior life never appears at all. That choice is not only technical, it is also political and emotional. It shapes who receives sympathy, who becomes scenery, and who the narrative treats as expendable.

Writers often talk about point of view as a question of craft. First person versus third, limited versus omniscient, tense and distance and free indirect style. All of that matters. However, underneath the technical vocabulary, a simpler question waits. Who holds the power to define the moment? The camera in the sentence doesn’t only show events. The camera decides whose version of events becomes real.

This article looks at that camera. It looks at how different points of view distribute authority across bodies on the page. It stays with the ethics of that distribution rather than the mechanics alone.

Distance, gaze, and the politics of looking

Every sentence answers three questions at once. Who looks. Who receives the look. Who stays invisible.

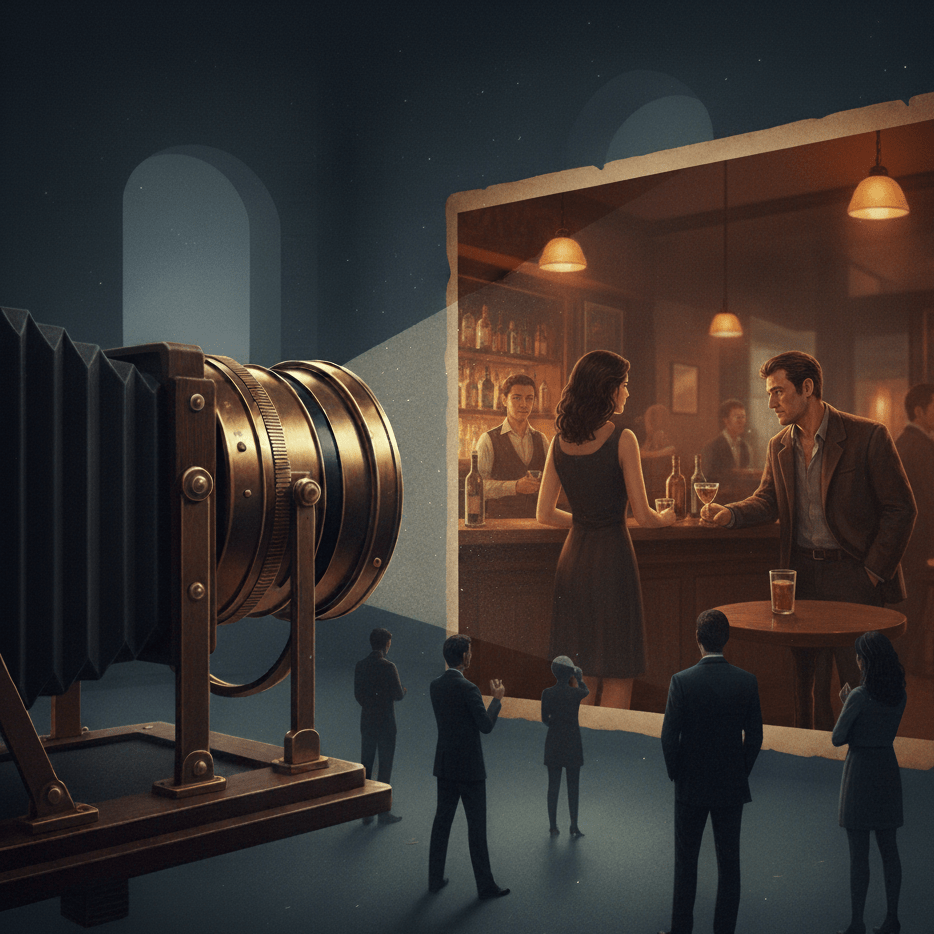

Imagine a scene in a bar. A woman stands at the counter and orders a drink. A stranger watches her from the other end of the bar. An author can choose any of these vantage points, yet the choice alters the power structure and, in fact, the scene itself.

From the stranger’s point of view, the sentence might say:

“He watched the woman at the bar and traced the curve of her back with his eyes.”

From her interior life, the sentence might say:

“She felt the stare on her shoulders and measured the distance to the door.”

From a neutral external view, the sentence might say:

“The woman ordered a drink, and a man at the corner looked over and watched her.”

Technically, all three versions use the same basic ingredients. One woman, one man, one bar. However, the camera settles in a different place each time. When the camera sits behind his eyes, the reader stands inside his desire. When the camera lives inside her awareness, the reader feels the cost of being watched. When the camera stands in the room between them, the reader observes both and joins neither completely.

That placement doesn’t only shift sympathy. It shifts agency. The person who owns the gaze often owns the verbs. The subject of the sentence names the world, assigns value, and selects which details matter. When the sentence says “He watched the woman at the bar and traced the curve of her back with his eyes,” he receives the verbs. He watches. He traces. She appears mainly as a surface for him to study. The reader may recognise the discomfort, yet the language still grants him the most active position.

The writer cannot exit this choice. Even a plain, stripped sentence carries a vantage point. A camera exists inside every line. The question is not whether the camera disappears. The question is whether the writer uses it with intention.

First person: intimacy and unreliable power

First person often feels honest. The narrator says I, and readers slip into that body with almost no resistance. That intimacy can feel like an ethical guarantee. It isn’t. First-person grants enormous authority to its speaker. The narrator can lie, distort, minimise harm, or re-frame exploitation as affection, and the reader receives that account as the default version of events unless the text clearly undermines it.

If a man describes his partner only through the lens of his desire, the language can turn her into a collection of responses to his presence. He may describe the way her body reacts when he enters a room, the way she softens when he speaks, the way her body fits against him. He may never tell you about her own wants or fears. Technically, this still counts as “deep” point of view. Emotion runs high. The camera stays in his world.

The ethical question is different. Whose interiority survives. Whose body becomes an object.

First-person can interrupt that pattern. A narrator can call attention to the limits of his own perspective. He can admit that he doesn’t know what his partner thinks. He can notice her flinch and recognise the way his desire blinds him. He can describe the moment when she pulls away, and he finally realises that he has treated her as a mirror instead of a person.

In that case, the power of first-person becomes useful. The narrative doesn’t just present what he sees. The narrative examines it. The camera looks at the look itself, and the sentence acknowledges the harm that a narrow view can cause.

Close third: the shoulder camera

Close third-person often operates like a camera at a character’s shoulder. The writer stays near one consciousness and lets the language absorb that character’s thoughts, biases, and preoccupations. Many novels use this mode to create a feeling of intimacy while still allowing some descriptive distance.

Because close third can glance away from the inner voice when needed, it tempts many writers into a pattern that feels neutral but still hides a power choice. In many scenes, the narrative will slip between lines that carry the character’s subjective lens and lines that present description as objective fact. When the camera moves without clear signals, the reader can lose track of whose interpretation currently dominates the scene.

For example, consider a detective in a crime novel who walks into an interview room and thinks about the suspect. The narrative might say:

“She stepped into the room and studied the girl in the plastic chair. The girl looked fragile and vain. The dress clung to her body in a way that begged for attention.”

These sentences relay the detective’s judgement, yet the narration may present that judgement as fact. The reader receives the description as a stable truth about the girl rather than a reflection of the detective’s biases. The verbs “looked” and “begged” sit on the page without being challenged.

A writer who wants to use close third with more ethical clarity can mark the subjectivity more openly.

“She stepped into the room and studied the girl in the plastic chair. The girl looked fragile to her, almost dainty. The tight dress read, to her eye, like something chosen to catch attention.”

The difference might seem small. However, the added phrases “to her” and “to her eye” place a frame around the judgement. The reader understands that this is one perspective, not the absolute truth. The camera doesn’t pretend to leave her shoulder. The camera admits its own angle may differ from hers.

Close third can also move the camera away from the character’s view when necessary. The writer can step outside for a line and grant the person under scrutiny a quiet interior life.

“She stepped into the room and studied the girl in the plastic chair. The girl folded her hands together, pressed her thumb against the edge of her nail, and held her breath until the first question arrived.”

The description doesn’t enter the girl’s thoughts, yet it grants her something more than a surface. The camera observes her gestures instead of her body as an object. Power begins to shift slightly toward her, even though the main interior focus of the book may remain with the detective.

Omniscient and the risk of aerial judgement

Omniscient narration offers a wide view. The camera can move freely through space and time. A writer can dive into multiple minds within the same scene, comment on them from outside, and provide historical context. This range can feel generous. However, the power imbalance increases when the narrative voice sounds like a universal authority.

In omniscient mode, the narrator often adopts a tone that resembles a lecturer, a chronicler, or a god. That voice can become dangerously comfortable with sweeping statements about groups of people. The narrator might describe “the women of the town” or “the men of the parish” as though these categories form uniform lines. Individuals inside those groups can vanish into archetypes, and the narrative can repeat the same objectifying patterns that exist in the culture outside the book.

The ethical question again returns to authority. Who receives the right to make such claims? If an omniscient narrator describes a queer character from above, and that description treats queerness as deviant or pitiable, the book endorses that view unless the text strongly resists it in other ways. The camera in that case rests inside the dominant ideology of the setting, and the narrator behaves like a servant of that structure.

Omniscient need not work that way. A narrator with full access can still treat marginalised characters with serious regard. The narrator can use that wide angle to reveal the gap between public judgement and private truth. The camera can move from the gossip in the town square to the interior of the queer character’s kitchen and show the ordinary reality that sits behind the rumours. The narrator can name prejudice and refuse to bow to it.

Regard instead of surveillance

The distinction between objectification and regard often appears in very small choices. Two sentences can describe the same detail and carry very different ethical weight.

“He watched the boy’s hands and gauged their usefulness.”

versus

“He watched the boy’s hands while he worked and tried to imagine the strain in his fingers.”

The first sentence reduces the hands to tools. The second at least attempts to follow sensation back into the boy’s body. Neither sentence enters the boy’s mind. However, the second tries to attend to labour rather than to the value of use alone.

A writer can ask simple questions during revision. Does this sentence describe a person as a set of functions? Does it treat their body as a resource for another character’s story? Does it grant them any interiority, even if the book never enters their thoughts directly?

Regard doesn’t require sentimentality. A narrative can look at a character honestly, and still refuse to turn that character into a symbol. The difference lies in whether the camera looks at them only to serve someone else’s arc.

Practical checks for writers

Writers can use point of view as a deliberate tool for redistributing power on the page. A few practical checks can help.

First, track who owns the verbs in the scene. List the main characters present and note how often each one appears as the subject of an active sentence. If one character consistently receives dynamic actions, while others receive only passive positions or decorative mentions, the camera likely favours that character in a way that flattens the rest.

Second, read a scene once with a specific question. Who remains faceless. That faceless character might be the server in a restaurant, the nurse in a hospital, the clerk in a shop, or the unnamed guard at a gate. Sometimes the story doesn’t need more from them. However, in many cases, one concrete detail or one small gesture can remind the reader that they possess their own life.

Third, examine any descriptions of bodies related to gender, race, or disability. Ask whose eyes supply the adjectives. Ask whether those adjectives treat the body as a spectacle or as a lived-in home. A character can notice another person’s beauty or desire them without peeling that person apart into isolated, consumable parts.

Fourth, consider a deliberate point of view shift in key scenes. If a scene currently sits inside the view of a character who holds social power, try rewriting it from inside the person who usually receives the stare. Even if the book never uses that alternate version, the exercise can reveal blind spots. The process can show where the current camera angle erases discomfort, risk, or resistance.

The sentence as an act of placement

Every sentence places the reader somewhere. On the street beside the character, inside their skull, across the room with folded arms. The placement always carries weight. When a writer makes that choice without reflection, the narrative often reproduces familiar hierarchies of power. Men receive the gaze in their eyes, women receive the gaze on their bodies. Queer and trans characters arrive only when the story requires conflict or tragedy.

Conscious point-of-view work can’t fix the world outside the page. However, it can refuse to mirror that world without question. Thoughtful use of the narrative camera can grant interiority to people who don’t receive it in other places. It can interrupt patterns that treat some bodies as default and others as scenery. It can deny the habit of turning desire into consumption.

When a writer places the camera, the writer makes a decision about power. That decision lives inside each line, whether the story whispers or shouts. To recognise that fact is not to burden the sentence with impossible responsibility. It’s to acknowledge that every sentence participates in a conversation about who counts. Once a writer sees that, point-of-view stops being only a technical choice and becomes a place where ethics and craft meet, right there on the page, inside the grammar of a single look.

Leave a comment